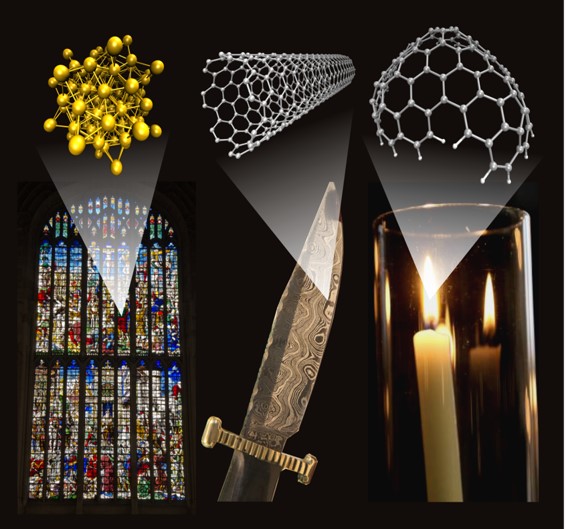

Nanotechnology conjures up images of tiny machines able to deliver drugs to the body, produce clean energy or take over the world – depending on who you talk to. The reality is that many of the nanostructures that scientists currently use in the lab have already been used for millennia.

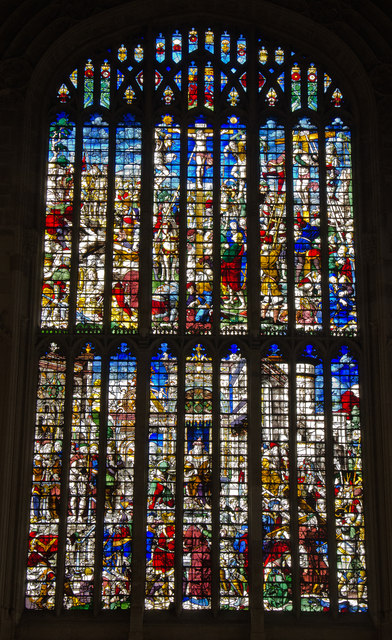

In the past, gold nanoparticles were used to produce brilliant reds in stained glass windows and nanoscale tubes were woven into Damascus steel to make strong, sharp swords. These technologies were used without full knowledge of the processes involved, or safety concerns; however, the recent breakthrough in nanotechnology is our understanding and control of nanoscale structures.

My colleagues and I at the Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology have found a common nanostructure that unites a variety of carbon materials, many of which are right under your nose. Water and air filters use activated carbon and vehicles produce soot – even your tennis racket and bike that contain carbon fibres.

You might be familiar with the layered structure of graphite: carbon atoms are arranged hexagonally in sheets that can easily glide past each other. This makes graphite a great material for pencil lead or a solid lubricant, but not as a filter or a bike frame. When graphite starts to become curved and interlinked is when the structure takes on its exceptional and diverse properties.

We ran quantum chemical calculations on the university’s supercomputers to understand what occurs when curvature is integrated into graphitic sheets through the replacement of a hexagonal ring of carbon with a pentagonal ring. This leads to a permanent bend in the structure that shuttles electrons from one side of the sheet to the other. This electric polarisation significantly increases the interaction of curvature-containing carbon material with molecules and itself, explaining how a relatively inert graphite can become strong and porous.

The next step for us is to explore how we can use our discoveries to reduce the emission of soot from vehicles, improve water filtration and improve the many carbon nanostructures that are right under our noses.

Jacob W. Martin

NanoDTC PhD Associate 2016

Image sources:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acero_damasceno_-_Toledo.JPG