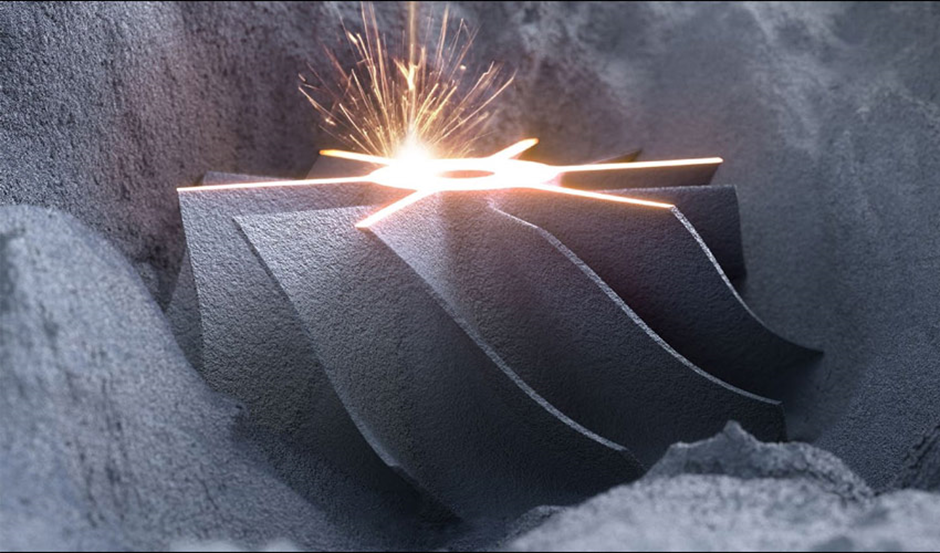

The ability to 3D print metal represents a paradigm shift in the way metal parts can be made. Conventionally, blocks or sheets of metal are machined down to the desired shape and fastened together as required to form everything you see around you. 3D printing works in a radically different way, instead of removing material and joining pieces together, parts are printed to have their final shape from the ground up. This opens up the possibility of creating complex geometries in whatever form you can imagine without the limitations of conventional manufacturing techniques.

Since its inception, 3D printing has been regarded as a sustainable approach to metal manufacturing. This is because it uses only the amount of material needed to build the final part, and thus employs fewer resources compared to conventional manufacturing methods. Moreover, the geometric freedom enabled by 3D printing allows structural parts to be re-designed with optimized shape and improved strength-to-weight ratio. Lightweight metal infrastructures—especially those employed in transportation and aerospace—are conducive to a more efficient fuel consumption and thus to a reduced carbon footprint. Unfortunately, these advantages are often overshadowed by the production costs associated with 3D printing, which scale with the amount of post-processing required to bring parts up to specification.

My goal is to develop a “print and use” additive manufacturing approach to produce metal alloys with outstanding mechanical properties without relying on any post-processing. For context, most metal alloys produced conventionally or by 3D printing require a post heat treatment step to increase their strength. This is a time- and energy-intensive process which is unavoidable if you want to produce the strongest possible parts.

To get around this I am investigating novel print strategies to control, directly during 3D printing, the crystalline phases and structure of the metal at the nanoscale. By varying laser power, scan speed, and layer thickness, I aim to induce an intrinsic heat treatment effect whereby the melting of higher layers in a part simultaneously heat treats lower layers to the optimal heat treating temperature. Integrating this heat treatment into the build process allows us to get around the age old problem of post processing parts.

Currently my material of choice for 3D printing is stainless steel. Like most metals, my stainless steel can be strengthened by heating it to somewhere below its melting temperature to relieve any internal stresses. With my particular steel, heating it to 500oC allows the small amounts of copper in the metal to diffuse through the microstructure and coalesce together to form nanoscale copper precipitates embedded within the metal. These precipitates act like anchors which hold the microstructure in place reducing its ability to deform resulting in superior mechanical properties.

The ability to “print and use” high performance steels may accelerate the adoption of metal 3D printing in industry and promote a sustainable metal manufacturing paradigm.

NanoDTC PhD Student, c2022