Humanity is rarely satisfied with something that’s ‘good enough’. Some people, at least, always want improvements on the current standard. Electric vehicles are one such example, and rightly so; they are a more environmentally friendly alternative than combustion engines (provided they are made and powered renewably, but that’s a separate issue), but currently they simply aren’t as practical as traditional combustion powered vehicles. They key issue most people care about is range; how far will I get before having to plug in again? To extend this, we need to pack more energy into a lighter package. This is where lithium-air batteries excel; extremely high energy capacities, taking in oxygen on discharge and releasing it again on charge.

In most batteries, such as the ubiquitous Li-ion batteries, there are two materials are known as the anode and cathode. In Li-ion batteries, the cathode, which is where the Li ion goes as the battery discharges, is usually some sort of metal oxide, often containing cobalt. The ethical and environmental issues associated with cobalt mining are well-documented, but even from a technical viewpoint this isn’t optimal, as this material has mass. For many applications, mass is a limiting factor on how much battery capacity we can have. This is where Li-air batteries shine. Rather than a solid cathode material, they use oxygen from the air to react with lithium ions during discharge, (mostly) eliminating the need for a cathode material. This results in Li-air batteries being far lighter than other battery technologies, with specific energy capacities potentially being comparable to petrol.

When Li-air batteries discharge, Li loses its electron which then can travel through an external circuit and be harnessed. The Li ion which is now charged can dissolve in the electrolyte, a liquid allowing for these ions to diffuse around without being stuck in place. The Li ions can then diffuse through a separator, which is to prevent short circuits within the battery, over to where it can react with oxygen. The reaction of Li ions with oxygen consumes electrons, and the net result is electrons going from the Li metal, through an external circuit, and into the reaction of Li ions with oxygen, forming a solid material called lithium peroxide.

Ut ornare lectus sit amet est placerat. Mauris a diam maecenas sed enim ut sem. Diam quis enim lobortis scelerisque. Pharetra vel turpis nunc eget lorem dolor sed. At varius vel pharetra vel turpis nunc eget lorem dolor. Mauris a diam maecenas sed enim ut sem viverra. Congue nisi vitae suscipit tellus mauris a diam. Consequat nisl vel pretium lectus quam. Venenatis a condimentum vitae sapien pellentesque habitant morbi tristique. Nibh ipsum consequat nisl vel. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit duis tristique. Augue neque gravida in fermentum et sollicitudin. Accumsan in nisl nisi scelerisque eu ultrices. Venenatis urna cursus eget nunc scelerisque viverra mauris in aliquam. Viverra nibh cras pulvinar mattis nunc sed blandit libero volutpat. Vitae elementum curabitur vitae nunc sed velit dignissim sodales ut. Elit eget gravida cum sociis natoque. Erat pellentesque adipiscing commodo elit at imperdiet dui accumsan sit.

Unfortunately, lithium peroxide is an electrical insulator, meaning once it forms it won’t carry electrons from the circuit to the Li ions and oxygen in the electrolyte, preventing further reaction. To circumvent this problem, Li-air batteries use a conductive material to act as the electrode, carrying the electrons to the electrolyte where the reaction can occur. This electrode is made to be extremely porous, like a sponge, so that lots of lithium peroxide can deposit within it, which corresponds to a large discharge capacity. The more lithium peroxide formed means that more electricity has flowed through the circuit.

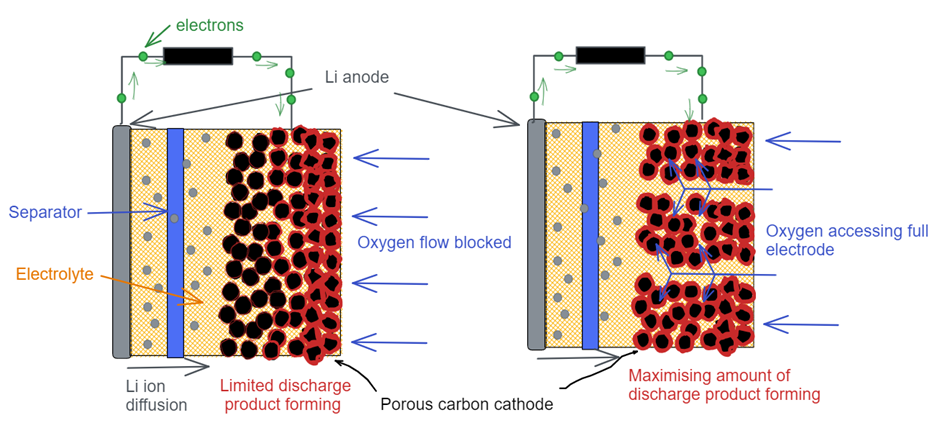

Things aren’t quite so simple, however. As lithium peroxide forms, the Li ions and oxygen dissolved in the electrolyte become depleted. To continue lithium peroxide formation, and thus battery discharge, we need more Li ions and oxygen to diffuse through our porous electrode. Usually, the limiting factor is oxygen, and so we must ensure oxygen diffuses through the whole electrode from the side where it is in contact with the oxygen. This is difficult to do evenly, and what we often see is that as the battery discharges, it will do so mostly by depositing lithium peroxide on the side of the electrode near the oxygen. Eventually, this blocks off all the pores on this side and oxygen can no longer diffuse through the whole electrode, and a large portion of the electrode is effectively wasted. This greatly reduces the amount of discharge product we could in theory form in our electrode, and thus limits the amount of energy we can get from our battery.

They key issue which I will be studying for my PhD is maintaining even gas diffusion through the whole electrode throughout discharge, allowing for efficient use of the whole space. One strategy we will be trying is using a laser to etch (relatively) big channels through an electrode made from woven carbon nanotubes which won’t get blocked and maintain constant gas diffusion throughout discharge. Developing on this, other porous carbon structures can be investigated, as well as ways to improve the sluggish oxygen reduction and evolution reactions which happen during discharge and charge of the batteries. The chemistry of Li-air batteries is complex and interdependent on the various components, and so there is a huge amount to learn about this system.

NanoDTC PhD Student, c2022